Quantum computing stands as a frontier of technological ambition, harnessing the enigmatic rules of particle physics to forge machines capable of tackling challenges far beyond the reach of traditional computers. The pursuit of such power has long been a daunting endeavour—experts have often pegged its arrival as decades distant, a tantalising yet elusive horizon.

Now, Microsoft claims a seismic shift in this timeline with a breakthrough centred on a new chip, driven by a material they’ve engineered: a topological conductor, or “topoconductor.” This innovation, the company asserts, could rival the semiconductor’s transformative legacy in computing history. Imagine a leap akin to the jump from vacuum tubes to silicon chips—only this time, it’s quantum mechanics rewriting the rules.

Yet, skepticism lingers. Experts caution that Microsoft’s bold claims demand more evidence. The research dazzles, but its true weight in the quantum race remains under scrutiny. Jensen Huang, Nvidia’s chief and a titan in the chip world, offered his own gauge in January, predicting “very useful” quantum computing in 20 years. Microsoft, however, bristles with urgency.

Chetan Nayak, a quantum hardware luminary at Microsoft, radiates confidence. “Many people have said that quantum computing, that is to say useful quantum computers, are decades away,” he declares. “I think that this brings us into years rather than decades.” His words signal a defiance of the old guard’s timeline—a gauntlet thrown down to doubters.

Travis Humble, who steers the Quantum Science Centre at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, acknowledges Microsoft’s advance. Prototypes will emerge faster, he agrees, but scaling them to conquer industrial-scale problems looms as the next hurdle. “The long-term goals for solving industrial applications on quantum computers will require scaling up these prototypes even further,” he notes. It’s a nod to progress, tempered by realism.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. Quantum computers promise to slash through calculations that would paralyse today’s systems for millions of years. Picture a drug discovery process slashed from decades to months, or battery designs produced overnight. These aren’t pipe dreams—they’re the tangible allure of quantum’s potential, spanning medicine, chemistry, and beyond.

Today’s “classical” computers—powering phones, laptops, and most modern tech—hit walls with certain problems. Quantum machines, by contrast, could smash through those barriers, offering rapid solutions to molecular modelling or cryptographic puzzles. It’s no wonder Silicon Valley’s giants are locked in a multi-billion-dollar sprint to claim this prize.

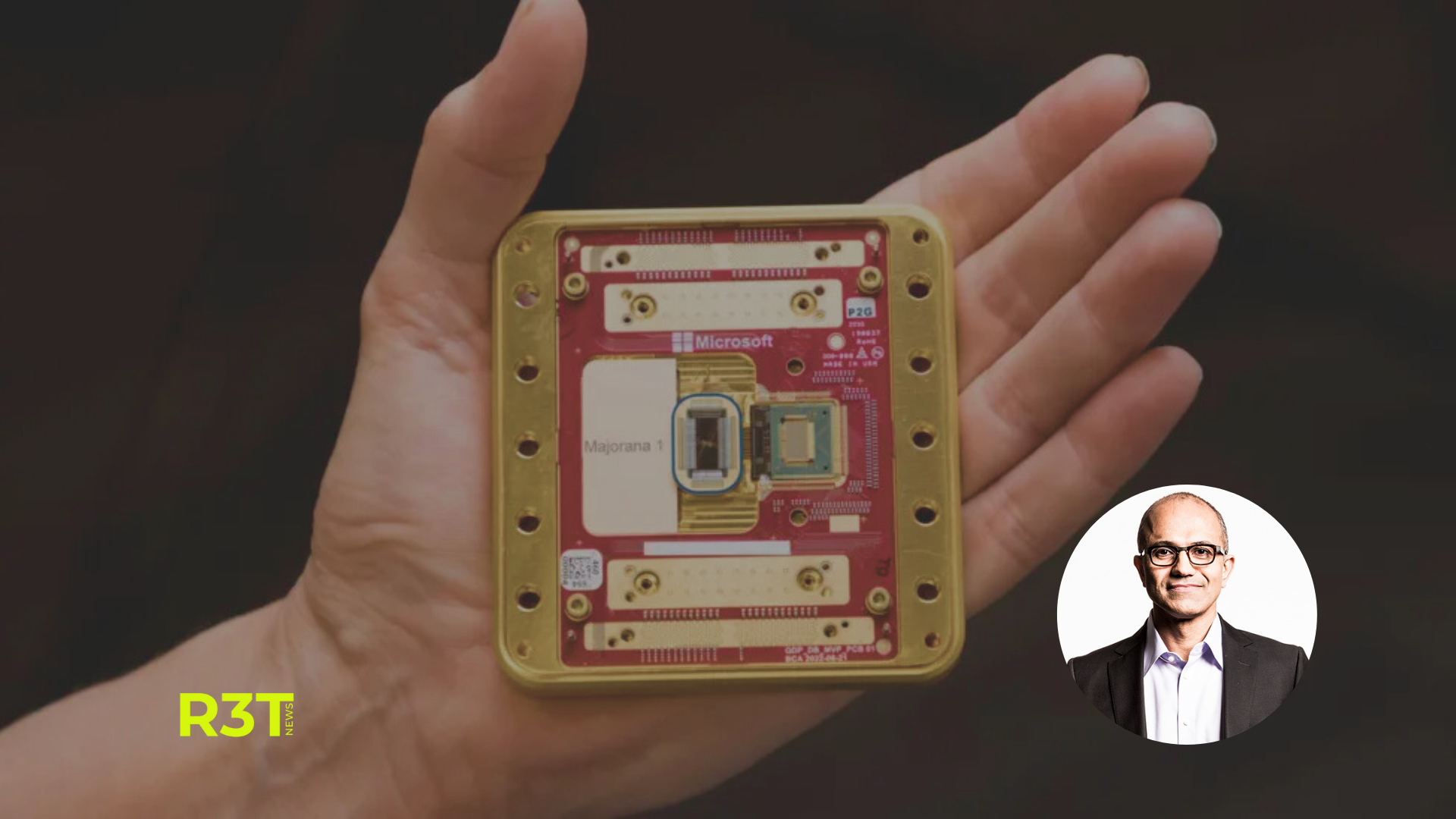

Microsoft charts a distinct course in this race. While rivals trumpet milestones—Google’s “Willow” chip made waves in late 2024—Microsoft has wagered on the topoconductor. This births a new state of matter, a “topological state” defying the familiar trio of gas, liquid, and solid. Until recently, it lived only in theory, tethered to the elusive Majorana—entities so tricky that a 2018 discovery claim famously unravelled.

The gamble was steep. Microsoft dubbed it “high-risk, high-rewards,” a phrase that now echoes as prophecy. “In the same way that the invention of semiconductors made today’s smartphones, computers and electronics possible, topoconductors and the new type of chip they enable offer a path to developing quantum systems,” the company proclaims. It’s a vision of quantum leaping from labs to life.

At the heart of this quest lies the qubit, quantum computing’s building block. Blazingly fast, yet fragile, qubits falter easily, prone to errors that stall progress. The more qubits a chip holds, the mightier its potential. Microsoft’s new chip boasts eight topological qubits—a modest tally compared to competitors’ hauls. But the company eyes a million-qubit future, a scale that could redefine computational power.

Not everyone’s sold. Paul Stevenson, a physicist at Surrey University, calls the work a “significant step” but urges caution. “Until the next steps have been achieved, it is too soon to be anything more than cautiously optimistic,” he warns. Progress, yes—but the summit remains distant.

Chris Heunen, a quantum programming expert at the University of Edinburgh, offers a brighter take. “This is promising progress after more than a decade of challenges, and the next few years will see whether this exciting roadmap pans out,” he tells the BBC. His words strike a balance: hope grounded in evidence.

So where does this leave us? Is Microsoft’s topoconductor the spark that ignites a quantum revolution, or a bold bet still proving its worth? Can a handful of qubits today truly scale to a million tomorrow? The answers will shape not just computing, but the frontiers of human discovery. For now, the race accelerates—and the world watches.